On May 20, Google unveiled significant enhancements to its AI-powered Search during the annual I/O conference, marking an evolution from the earlier “AI Overviews.” These advancements include deeper reasoning, multimodal […] Read More

Best Practices for Responsive Search Ads in Today’s Google Ads Optimization Score Environment

As much as I miss Expanded Text Ads – 3 years later Responsive Search Ads (RSAs) are a core part of any modern Google Ads strategy. With RSAs, you can […] Read More

The Ultimate Guide to SEO for Architects

In today’s digital-first world, having a strong online presence isn’t just nice to have for architectural firms—it’s essential. As potential clients increasingly turn to search engines to find architectural services, […] Read More

Optimizing a Google Business Profile for Architects: A Step-by-Step Guide

For architects, a well-optimized Google Business Profile (GBP) is more than just an online listing—it’s a powerful tool for attracting local clients, showcasing your expertise, and enhancing your firm’s credibility. […] Read More

Analyze SERPs for Better Keyword Research

Diving into Search Engine Results Page (SERP) analysis is a must-do for SEO pros and marketers aiming to pick the best keywords and understand the competitive scene and user intent […] Read More

Link Building Strategies for 2025

Backlinks continue to be a cornerstone of SEO success, and as we move into 2025, the way we approach link-building is evolving. With insights from recent Google search trends and […] Read More

A Quick Key for Social Media Image Sizes

Every social media platform has its own specific image size requirements, which can make it challenging to keep track of the ideal dimensions for each. To simplify things, we’ve compiled […] Read More

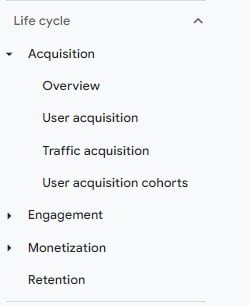

Finding Your Google Ads Data in GA4

Google Analytics 4 has drastically changed the ability to pull data from your website performance and specifically your campaign performance. For years we were trained in the usability and conventions […] Read More

How Small Businesses Can Use AI for SEO

With the rise of AI in digital marketing, small businesses have gained access to powerful tools that simplify SEO tasks and help them compete with larger enterprises. By incorporating AI […] Read More